1954

Oliver

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Oliver

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas

In the 1950s, school segregation was

widely accepted throughout the nation. In fact, it was required by law

in most southern states. In 1952, the Supreme Court heard a number of

school-segregation cases, including Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas. It decided unanimously in 1954 that segregation

was unconstitutional, overthrowing the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson

ruling that had set the "separate but equal" precedent.

1955

Montgomery

Bus Boycott Montgomery

Bus Boycott

Rosa Parks, a 43-year-old black

seamstress, was arrested in Montgomery, Alabama, for refusing to give

up her bus seat to a white man. The following night, fifty leaders of

the Negro community met at Dexter Ave. Baptist Church to discuss the

issue. Among them was the young minister, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The leaders organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which would deprive

the bus company of 65% of its income, and cost Dr. King a $500 fine or

386 days in jail. He paid the fine, and eight months later, the

Supreme Court decided, based on the school segregation cases, that bus

segregation violated the constitution.

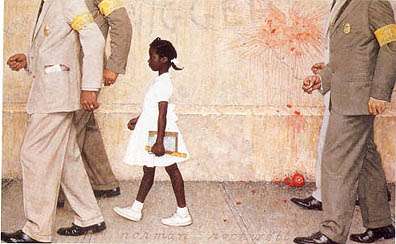

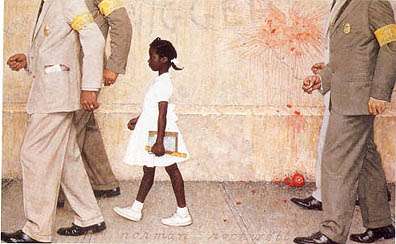

1957

Desegregation

at Little Rock, Arkansas Desegregation

at Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock Central High School was to

begin the 1957 school year desegregated. On September 2, the night

before the first day of school, Governor Faubus announced that he had

ordered the Arkansas National Guard to monitor the school the next

day. When a group of nine black students arrived at Central High on

September 3, they were kept from entering by the National Guardsmen.

On September 20, judge Davies granted an injunction against Governor

Faubus and three days later the group of nine students returned to

Central High School. Although the students were not physically

injured, a mob of 1,000 townspeople prevented them from remaining at

school. Finally, President Eisenhower ordered 1,000 paratroopers and

10,000 National Guardsmen to Little Rock, and on September 25, Central

High School was desegregated.

1960

Sit-in

Campaigns Sit-in

Campaigns

After having been refused service at the

lunch counter of a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, Joseph

McNeill, a Negro college student, returned the next day with three

classmates to sit at the counter until they were served. They were not

served. The four students returned to the lunch counter each day. When

an article in the New York Times drew attention to the students’

protest, they were joined by more students, both black and white, and

students across the nation were inspired to launch similar protests.

1961

Freedom

Rides Freedom

Rides

In 1961, bus loads of people waged a

cross-country campaign to try to end the segregation of bus terminals.

They nonviolent protest, however, was brutally received at many stops

along the way.

1962 1962

University of Mississippi Riot

President Kennedy ordered Federal

Marshals to escort James Meredith, the first black student to enroll

at the University of Mississippi, to campus. A riot broke out and

before the National Guard could arrive to reinforce the marshals, two

students were killed.

1963

Birmingham

Birmingham,

Alabama was one of the most severely segregated cities in the 1960s.

Black men and women held sit-ins at lunch counters where they were

refused service, and "kneel-ins" on church steps where they

were denied entrance. Hundreds of demonstrators were fined and

imprisoned. In 1963, Dr. King, the Reverend Abernathy and the Reverend

Shuttles worth lead a protest march in Birmingham. The protesters were

met with policemen and dogs. The three ministers were arrested and

taken to Southside Jail. Birmingham,

Alabama was one of the most severely segregated cities in the 1960s.

Black men and women held sit-ins at lunch counters where they were

refused service, and "kneel-ins" on church steps where they

were denied entrance. Hundreds of demonstrators were fined and

imprisoned. In 1963, Dr. King, the Reverend Abernathy and the Reverend

Shuttles worth lead a protest march in Birmingham. The protesters were

met with policemen and dogs. The three ministers were arrested and

taken to Southside Jail.

1963 1963

March on Washington

Despite worries that few people would

attend and that violence could erupt, Philip Randolpf and Bayard

Rustin organized the historic event that would come to symbolize the

civil rights movement. A reporter from the Time wrote, "no one

could ever remember an invading army quite as gentle as the two

hundred thousand civil rights marchers who occupied Washington."

1965

Bloody Sunday

Outraged

over the killing of a demonstrator by a state trooper in Marion,

Alabama, the black community of Marion decided to hold a march. Martin

Luther King agreed to lead the marchers on Sunday, March 7, from Selma

to Montgomery, the state capital, where they would appeal directly to

governor Wallace to stop police brutality and call attention to their

struggle for suffrage. When Governor Wallace refused to allow the

march, Dr. King went to Washington to speak with President Johnson,

delaying the demonstration until March 8. However, the people of Selma

could not wait and they began the march on Sunday. When the marchers

reached the city line, they found a posse of state troopers waiting

for them. As the demonstrators crossed the bridge leading out of

Selma, they were ordered to disperse, but the troopers did not wait

for their warning to be headed. They immediately attacked the crowd of

people who had bowed their heads in prayer. Using tear gas and batons,

the troopers chased the demonstrators to a black housing project,

where they continued to beat the demonstrators as well as residents of

the project who had not been at the march. Outraged

over the killing of a demonstrator by a state trooper in Marion,

Alabama, the black community of Marion decided to hold a march. Martin

Luther King agreed to lead the marchers on Sunday, March 7, from Selma

to Montgomery, the state capital, where they would appeal directly to

governor Wallace to stop police brutality and call attention to their

struggle for suffrage. When Governor Wallace refused to allow the

march, Dr. King went to Washington to speak with President Johnson,

delaying the demonstration until March 8. However, the people of Selma

could not wait and they began the march on Sunday. When the marchers

reached the city line, they found a posse of state troopers waiting

for them. As the demonstrators crossed the bridge leading out of

Selma, they were ordered to disperse, but the troopers did not wait

for their warning to be headed. They immediately attacked the crowd of

people who had bowed their heads in prayer. Using tear gas and batons,

the troopers chased the demonstrators to a black housing project,

where they continued to beat the demonstrators as well as residents of

the project who had not been at the march.

Bloody Sunday received national

attention, and numerous marches were organized in response. Martin

Luther King, Jr. lead a march to the Selma bridge that Tuesday, during

which one protestor was killed. Finally, with President Johnson’s

permission, Dr. King led a successful march from Selma to Montgomery

on March, 25. President Johnson gave a rousing speech to congress

concerning civil rights as a result of Bloody Sunday, and passed the

Voting Rights Act within that same year.

|

Oliver

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas

Oliver

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Montgomery

Bus Boycott

Montgomery

Bus Boycott Sit-in

Campaigns

Sit-in

Campaigns Freedom

Rides

Freedom

Rides 1962

1962 Birmingham,

Alabama was one of the most severely segregated cities in the 1960s.

Black men and women held sit-ins at lunch counters where they were

refused service, and "kneel-ins" on church steps where they

were denied entrance. Hundreds of demonstrators were fined and

imprisoned. In 1963, Dr. King, the Reverend Abernathy and the Reverend

Shuttles worth lead a protest march in Birmingham. The protesters were

met with policemen and dogs. The three ministers were arrested and

taken to Southside Jail.

Birmingham,

Alabama was one of the most severely segregated cities in the 1960s.

Black men and women held sit-ins at lunch counters where they were

refused service, and "kneel-ins" on church steps where they

were denied entrance. Hundreds of demonstrators were fined and

imprisoned. In 1963, Dr. King, the Reverend Abernathy and the Reverend

Shuttles worth lead a protest march in Birmingham. The protesters were

met with policemen and dogs. The three ministers were arrested and

taken to Southside Jail.

1963

1963 Outraged

over the killing of a demonstrator by a state trooper in Marion,

Alabama, the black community of Marion decided to hold a march. Martin

Luther King agreed to lead the marchers on Sunday, March 7, from Selma

to Montgomery, the state capital, where they would appeal directly to

governor Wallace to stop police brutality and call attention to their

struggle for suffrage. When Governor Wallace refused to allow the

march, Dr. King went to Washington to speak with President Johnson,

delaying the demonstration until March 8. However, the people of Selma

could not wait and they began the march on Sunday. When the marchers

reached the city line, they found a posse of state troopers waiting

for them. As the demonstrators crossed the bridge leading out of

Selma, they were ordered to disperse, but the troopers did not wait

for their warning to be headed. They immediately attacked the crowd of

people who had bowed their heads in prayer. Using tear gas and batons,

the troopers chased the demonstrators to a black housing project,

where they continued to beat the demonstrators as well as residents of

the project who had not been at the march.

Outraged

over the killing of a demonstrator by a state trooper in Marion,

Alabama, the black community of Marion decided to hold a march. Martin

Luther King agreed to lead the marchers on Sunday, March 7, from Selma

to Montgomery, the state capital, where they would appeal directly to

governor Wallace to stop police brutality and call attention to their

struggle for suffrage. When Governor Wallace refused to allow the

march, Dr. King went to Washington to speak with President Johnson,

delaying the demonstration until March 8. However, the people of Selma

could not wait and they began the march on Sunday. When the marchers

reached the city line, they found a posse of state troopers waiting

for them. As the demonstrators crossed the bridge leading out of

Selma, they were ordered to disperse, but the troopers did not wait

for their warning to be headed. They immediately attacked the crowd of

people who had bowed their heads in prayer. Using tear gas and batons,

the troopers chased the demonstrators to a black housing project,

where they continued to beat the demonstrators as well as residents of

the project who had not been at the march.